Raised Embroidery

Often I am asked if I have a favorite textile. This is like asking a mom which is her favorite child. Each is unique, each has positive (and negative attributes), each brings a different aesthetic. Asked if I have a favorite textile technique, the answer is immediate. I have always favored embroidery. I admit to having tried (with varying degrees of success) sewing clothes and home goods, rug braiding and hooking, quilting, crochet and knitting. I have even dabbled in paper-making and basket weaving, which I consider to be cousins of textiles on the textile family tree. But after many, many years of working with all forms of textiles and their production I am still drawn to the art of embroidery.

It is not that I am particularly adept at embroidery techniques. I love the portability, being able to take with me small pieces of work when I travel. But I especially love the richness of the finished product, the variety of the stitches, the assortment of fibers, and the ability of the textile artists to create their own unique works of art.

My textile library is filled with editions of embroidery history, technique, ethnic and contemporary. Also, of course, are the many volumes of examples and instructions waiting for me to stitch.

The Embroiderer’s Flowers,

Thomasina Beck, David and Charles, 1992

The Embroiderer’s Garden,

Thomasina Beck, David and Charles

Like all trends and pastimes, embroidery has seen a roller coaster history. While never being completely absent, there are periods in which embroidery was considered an important textile art form, only to give way to other techniques. One case in point is the needlework commonly called “Stump Work”. I consider this to be a rather unfortunate title. Originally, this type of embroidery was called “Raised Work” or “Embosted Work” It was in Victorian times that the term stumpwork was used. Perhaps it pertained to the use of wooden stumps or moulds which, when padded offered an element in relief, or it could have come from the printed designs, stamped on the ground fabric. The French word “estompe” means embossed, and is a likely contender.

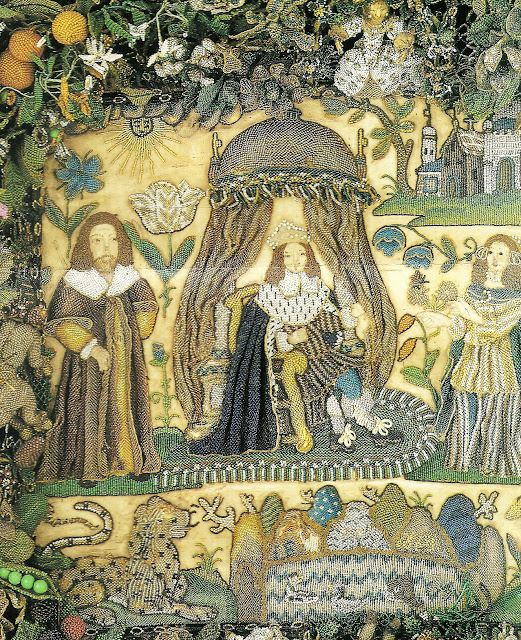

When speaking of the history of raised work, it is a short one. It reached the height of its popularity between 1640 through 1680. There are earlier samples worked by professional embroiderers (Brioders) with three dimensional design elements.

The themes for these works were often stories from the Old Testament or depictions of court life. The main pattern was often the work of a professional designer. There were even kits available. One of the most delightful features of these embroideries was the inclusion of various forms of flora and fauna, realistic, as well as fanciful. These lesser elements were usually not to scale. Therefore a pea pod might be as large as a rabbit. Patterns were available in collections printed for embroiderers. Relief elements, in addition to the wooden forms for bodies and facial features, were made from wrapped wire, beads and other embellishments. Some motifs were directed embroidered onto the ground fabric in a variety of stitches while other were created separately as “slips” and later added to the scene.

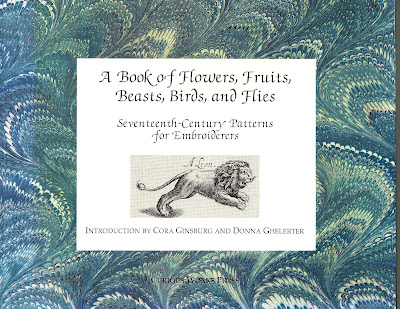

A Book of Flowers, Fruits, Beasts, Birds and Flies –

Seventeenth-Century Patterns for Embroiderers, Curious Works Press, 1995

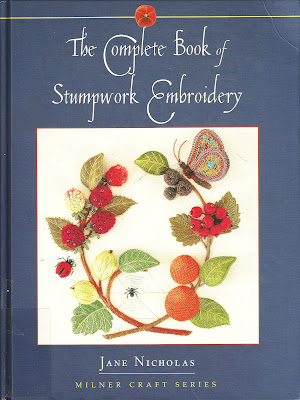

The Complete Book of Stumpwork Embroidery, Jane Nicholas,

Sally Milner Pub.,

Boward NSW, Australia, 2005

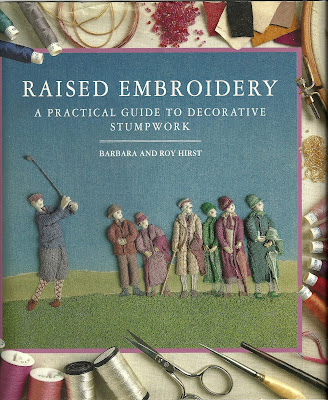

Raised Embroidery- a Practical Guide of Decorative Stumpwork,

Barbara and Roy Hirst, Merchurst LTD, 1993

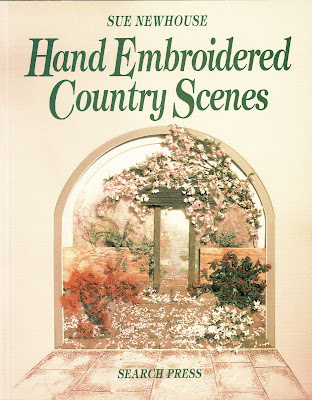

Hand Embroidered Country Scenes, Sue Newhouse,

Search Press, 1997

My next project might well be a small stumpwork, perhaps the view of my patio and the grape vines growing across the portal. Maybe not.

Leave a Reply